Middleton St. George ….. 1942

I attended a two week course at the RAF School on the Rolls Royce Merlin aircraft engine factory in Derby.

This was the best and most interesting course that I have ever participated in.

Next, the squadron moved a short distance east and took over half of a very large former RAF

base, named Middleton St. George, situated about half way between Darlington and Stockton.

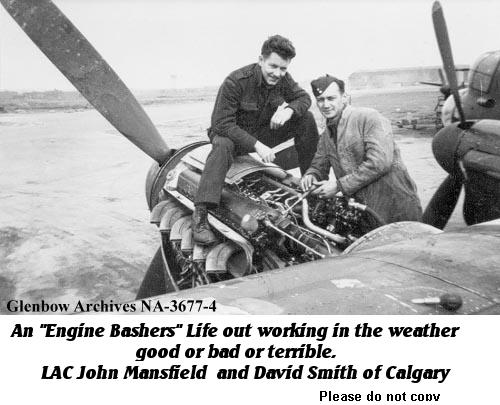

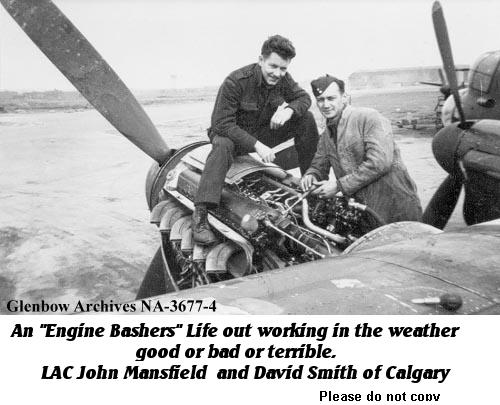

There were no hangers to perform major repairs, so all work had to be done out in the open.

This was normal for servicing and minor work, but it did create some hardships completing major repairs in cold weather.

We lived in steel nissen huts with about 14 men per hut; there was only one very small stove and a minimal allotment of coal.

As I was corporal in charge of our hut, when the cold weather arrived, I detailed one man per day to remain there and keep the

fires going. To achieve this they were obliged to steal coal or obtain wood from anywhere they could, for example, farmers' fence posts!

Arrival of the Halifax

As we were soon to receive new Halifax planes, I managed to spend a week or so with Ken

Johnston at another base where I learned quite a bit from him. When I returned to our

squadron, I was promoted to sergeant and put in charge of our first Halifax. This kite was being

used to train aircrew changing from two-engined to four-engined bombers. As there was still

a shortage of flight engineers, I was asked to serve as an acting flight engineer on training flights

around the British Isles. I did that for a couple of weeks and found it interesting, but my true

commitment was keeping the aircraft in reliable flying condition.

Our squadron was soon fully equipped with Halifax bombers. Initially I was in charge of only

one kite, but soon I had responsibility for two. They required considerable maintenance to keep

them in shape. They could take a lot of punishment but they couldn't fly very high or very fast,

so we actually lost a lot of them. They did however, carry a large bomb load and managed in

spite of the losses, to do quite a bit of damage to their targets.

That summer a crew of mechanics went south to the Salisbury Plains to replace two engines on one of our kites,

which had made an emergency landing at an RAF aerodrome called Middle Wallop. I had papers that authorized me

to easily obtain food, accommodation, petrol and supplies at any military establishment in the British Isles while on

this trip. Not bad for a mere sergeant! Our CO had supplied me with a fair amount of beer money for the crew.

I was also able to secure a bottle of scarce whisky from him occasionally. My truck and trailer driver on this trip,

Bill Tanner, was a 6'4" Cape Breton Islander, whose size we appreciated after getting into a scrap with a bunch of

English soldiers at a dance. We discovered we weren't universally popular on army bases, especially if they were

holding a dance, because the British, girls seemed to favour us.

A Change in Chain of Command

The senior NCO's in charge of flights were still RAF men, but that was soon to be change.

In the middle of the summer of 1943 I was promoted to the rank of Flight Sergeant and had

responsibility for running the ground crews of "A" flight. This consisted of 12 operational

aircraft, six sergeants, 12 corporals and 80-90 aircraft men. I had a great bunch of men, many

of them farm boys familiar with repairing and they took great pride in keeping their kites in top shape.

They would work all hours of the day or night without any urging from me. I remember changing an

n engine cylinder block one night outside in a snowstorm (the hangers were full) to have the kite

ready in time for its next operation. This was a very delicate job but we managed with the help

of a crane operator, night lights and tarpaulins.

My flight office (shack) was situated about a mile away from the main buildings, so we were all

issued bicycles. I also had a small truck and two WAAF truck drivers assigned to my flight.

All our kites were scattered about on hard standings connected to the perimeter roads.

The men built frames and put tarpaulins over them to create shelters; we all heated our shacks in the winter

by burning used engine oil, sometimes thinned with petrol (gasoline), in home-made stoves.

A couple of these shelters burned down when too much petrol was used.

Groundcrew personnel used to take turns flying with the planes on frequent test or training

flights around the local area. Hedge hopping was a very exciting experience, although it scared

the hell out of the cattle in the fields and aroused the ire of the farmers. One day when it was

my turn I allowed a new man to go in my place because he had not yet been up. The plane

crashed and all on board were killed.

At the controls

One of the most interesting of our escapades, at least to me, was when we "flew" a Halifax out

of the mud. The soil there was gumbo clay which became very soft after heavy rains. New

pilots had a bad habit of running off the perimeter track when taxiing back to their dispersal

points after a bombing mission. I am not faulting them, it was usually dark, there were no

lights, and they would be tired and possibly damaged. Still, it created a lot of extra work for

us. The kite would be bogged down a foot or more in the mud, perhaps 50' off the hard

surfaced track. It took two of the heavy petrol bowsers (tanker trucks) with their winches to pull

these heavy kites out and if several got stuck on the same night, it would be many hours before

we secured them back on their dispersal stands for repair. One night this did happen; only one

of ours was stuck, but several of the other squadron's planes were in the mud and they got to

the bowsers first. The aircraft's groundcrew had dug the necessary trenches in front of the

wheels and lined them with planks. It was early in the morning and no one was around except

the mechanics, so I said to Tiny Shultis, the big corporal of that crew, "Let's fly the damned

thing out, are you game?" He agreed, so we warmed up the four 1400 horse power V-12 Rolls

Royce Merlins. I took the control stick and Tiny handled the throttle levers. I said "open the

throttles half way"; the plane shook a bit but did not budge. "Open three quarters", still it

would not move; "Open all the way, Tiny"; he did and the machine shot out of there like a

greyhound let off its leash. We blasted across the perimeter track and beyond into the open field

with those throttles wide open, and Tiny frozen in shock. I yelled at him and beat on his hands;

he finally came to his senses just seconds before we actually took off, then we almost became

stuck again as it slowed down so quickly in the muddy field. We opened up the throttles again

part way. I managed to get her turned around and stopped on the perimeter track on the third

try. Tiny and I got out of the kite with white faces and shaking limbs and both decided to give

up on ground flying. Of course we were not allowed to taxi these machines, none of us had

ever received adequate training and we could have been severely reprimanded, but fortunately

no one reported us.

Less then a warm welcome

I was the only one in our family who stayed in one place, therefore Dad (stationed in England

with the Forestry Corp) and my two brothers, Jim, in the Artillery and Bill, in the Army, would

visit me occasionally on their leaves. I could easily arrange for accommodation and meals. I

was usually able to find air force sergeant's jackets for them to wear so we would be permitted

to eat in the sergeant's mess without too many hassles. However, the first time that 19 year old,

Army private Bill came visiting, I took him to the mess still wearing his own uniform. A senior

RAF sergeant ordered me to remove him at once. I told him to go to hell and that there

were ways of dealing with the likes of him. He backed off then, but he did put me on charge

for disobeying a senior officer, threatening a senior officer, and having unauthorized personnel

in the sergeants' mess. I was marched before the commander of the entire station, Group

Captain "Shakey" Ross, a Canadian who had served with the RAF during the Battle of Britain.

He told me I should not have behaved as I had, but because I had a good record, he wasn't

going to spoil it. He then inquired about my younger brother and suggested that I find an air

force sergeant's tunic for him. The RAF sergeant major stood with his mouth open, ignored

by the commanding officer. When we were dismissed he said to me, "I'll never understand you

Canadians, you have no sense of military discipline, no matter what rank you are". I said he

was absolutely right and should remember that next time he put anyone on charge.

My brother Jim was sent to England from Italy to attend a commissioned officers training course. He and

a friend on the same course, were granted leave before returning to Italy. They came to

Middleton St. George sporting their brand new lieutenants uniforms, hungry, thirsty and flat

broke. I billeted them in the sergeants' mess, secured them air force sergeants' tunics and a

couple of bicycles. They had a great time eating heartily and drinking on my money. I even

sent them up on a couple of training flights. I was sorry to see them go; Jim was the only one

of us that reached commissioned rank. Much later he was the colonel in charge of the Regina

artillery reserves.

Dad dropped in a few times; once he found me in the hospital with a jaw infection caused by

contaminated pain killers used when pulling a wisdom tooth. He stayed for a few days until I

was on the road to recovery and cheered me up immensely, relating all the happenings in the

family.

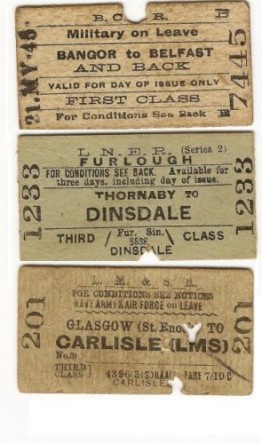

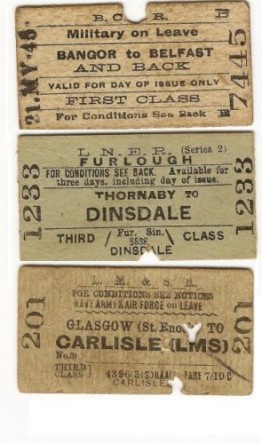

For Canadian servicemen stationed in Britian being on leave gave them a chance to visit

relatives who they may never have had a chance to ever see otherwise. With his father stationed in

England acting as guide, Fred was able to meet with two of his uncles. One was a London, Harley Street physician

and the other a sea captain living in Devonshire, men who were highly thought of in their communities and

both able to show him the sights of these two vastly diffent landscapes and lifestyles in Britian.

This was normal for servicing and minor work, but it did create some hardships completing major repairs in cold weather.

We lived in steel nissen huts with about 14 men per hut; there was only one very small stove and a minimal allotment of coal.

As I was corporal in charge of our hut, when the cold weather arrived, I detailed one man per day to remain there and keep the

fires going. To achieve this they were obliged to steal coal or obtain wood from anywhere they could, for example, farmers' fence posts!

This was normal for servicing and minor work, but it did create some hardships completing major repairs in cold weather.

We lived in steel nissen huts with about 14 men per hut; there was only one very small stove and a minimal allotment of coal.

As I was corporal in charge of our hut, when the cold weather arrived, I detailed one man per day to remain there and keep the

fires going. To achieve this they were obliged to steal coal or obtain wood from anywhere they could, for example, farmers' fence posts! My flight office (shack) was situated about a mile away from the main buildings, so we were all

issued bicycles. I also had a small truck and two WAAF truck drivers assigned to my flight.

All our kites were scattered about on hard standings connected to the perimeter roads.

The men built frames and put tarpaulins over them to create shelters; we all heated our shacks in the winter

by burning used engine oil, sometimes thinned with petrol (gasoline), in home-made stoves.

A couple of these shelters burned down when too much petrol was used.

Groundcrew personnel used to take turns flying with the planes on frequent test or training

flights around the local area. Hedge hopping was a very exciting experience, although it scared

the hell out of the cattle in the fields and aroused the ire of the farmers. One day when it was

my turn I allowed a new man to go in my place because he had not yet been up. The plane

crashed and all on board were killed.

My flight office (shack) was situated about a mile away from the main buildings, so we were all

issued bicycles. I also had a small truck and two WAAF truck drivers assigned to my flight.

All our kites were scattered about on hard standings connected to the perimeter roads.

The men built frames and put tarpaulins over them to create shelters; we all heated our shacks in the winter

by burning used engine oil, sometimes thinned with petrol (gasoline), in home-made stoves.

A couple of these shelters burned down when too much petrol was used.

Groundcrew personnel used to take turns flying with the planes on frequent test or training

flights around the local area. Hedge hopping was a very exciting experience, although it scared

the hell out of the cattle in the fields and aroused the ire of the farmers. One day when it was

my turn I allowed a new man to go in my place because he had not yet been up. The plane

crashed and all on board were killed.