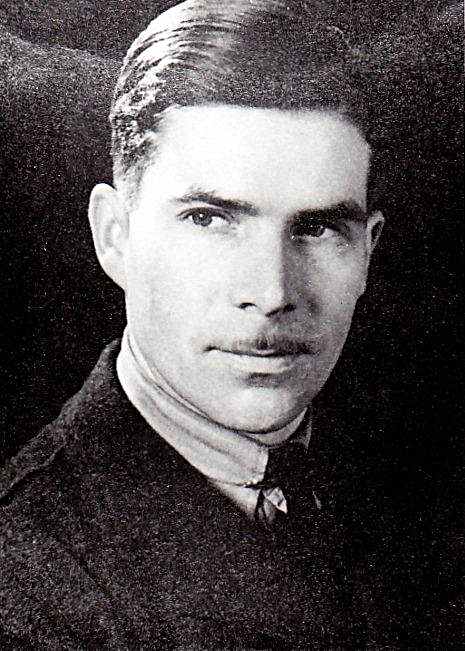

By way of an introduction, I had met Mr. Sinclair a number of

times when I was much younger. Sinc, as my father called him was the Flight

Sergeant on “A” Flight, the same Flight as my father was a Sergeant in.

As far as I can remember he was the only one of my father’s

squadron that I ever met. My father held “Sinc” in very high regard both as

a person and as a mechanic. Fred Sinclair had developed his

mechanical skills at the early age of twelve, while being with his father who was a Forest Ranger

for the Manitoba Forest Service. Maintaining the pumps responsible for

fighting forest fires was his starting point, in the years to follow his experience as a mechanic were to grow.

Farm equipment, motorcycles and of course automobile repairs would make him the

type of skilled man the RCAF would be looking for during the coming war years.

But this was not be or at least not immediately. For as many would find out,

the RCAF was not ready for the flood of able men that applied so early on. Like a number of future

Moosemen Fred Sinclair would have to wait until the reality of war took hold in the Canadian military.

In time he was called up and told to report to No.2 Manning Depot Brandon.

Where we take up his story as he tells it.

"As a group of 15 potential aero engine mechanics, we were sent to Brandon Manitoba

where we were fitted (somewhat) with uniforms, and endured six weeks of basic

military training. War efforts were just becoming organized. There were no

military eating facilities, so we ate all our meals at the Olympic Cafe.

After basic training ,which was the only army type training I ever received,

we were sent to the aero engine school operating in a confiscated insane asylum

(no comments please). This was No. 1 Technical Training, located just outside

St. Thomas, Ontario which is between London Ontario and Lake Erie. We trained

there that summer in all the basic types of aero engines.

we were sent to the aero engine school operating in a confiscated insane asylum

(no comments please). This was No. 1 Technical Training, located just outside

St. Thomas, Ontario which is between London Ontario and Lake Erie. We trained

there that summer in all the basic types of aero engines.

I bought a beat up old Pontiac and was able to visit Bernice again and relatives

on weekends. After graduating with a fairly good standing, I was posted to the

newly-opened airdrome near Dunnville, designated as No.6 SFTS (Service Flying

Training School) where budding pilots were taught to fly Harvards and Yales.

I was there for about a year and a half, and during the first year was promoted

to corporal. Duties included keeping the many training aircraft repaired,

serviced including major servicing and engine replacements.

Bernice and I became engaged in the early spring of 1941 and were married

on June 17th, my 25th birthday. Very early that morning, I set the stage by

shaking up the town of Cayuga. I had become friends with one of the pilot

instructors and he and I went up at 7:00 a.m. and really did a number,

diving down and practically taking the roof off Bernice' s family home. Of course

this was illegal and there were many protests in the local paper and to

the Commanding Officer at No. 6, but we had gone so fast it was impossible

for anyone to obtain the identifying number of the plane, so luckily we

remained anonymous.

After thier military type wedding, the couple travelled in Fred’s new Essex coupe complete with two spares adorning the front fenders as well as the usual newly wed adornments of tin cans and streamers attached to the car. With his brother Jim hitching a ride to Toronto in the rumble seat, where they met with the local police over a minor infraction, which the police on sizing up the situation decidied to just let them go.

When we returned to Dunnville I rented a truck and hauled what few possessions we

had to Bernice's family home in near by Cayuga. I sold the car for $100 and gave the money to

Bernice. We had an emotional parting at the train station in Hamilton and we didn't see each

other for three and a half years. In Toronto there was an unexpected delay for a day so I was able

to visit my sister Dorothy, who was looking after some children for a couple in

New Toronto. The next day I boarded a troop train for Halifax.

We were in Halifax about a week before our escort destroyers arrived. Our total

convoy consisted of two troop ships and two old American destroyers on loan to the

Canadian Navy.

We were capable of maintaining 22 knots therefore we could have crossed the

Atlantic very fast, but took eight days because we sailed from the Azores north to Iceland dodging

U-boat packs.One day while we were attending a movie in the main recreation room of our

transport ship the the former luxury liner Alcantara

the ship turned and

heeled so sharply that the piano slid right through the wall out onto the deck.

A couple of days into our voyage, we encountered a severe storm and practically

everyone suffered severe sea sickness. In our cabin of 16, only two of us

remained healthy. We were responsible for gathering food for all the others.

We continued

collecting meals for 16 men, eating most of it ourselves. I became friendly

with one of the

ship's sailors who took me on a tour of the entire vessel. The huge turbines

were most

interesting to me. At Iceland our security was assumed by two Royal Navy

destroyers who

accompanied us south to the river Clyde in Scotland.

the ship turned and

heeled so sharply that the piano slid right through the wall out onto the deck.

A couple of days into our voyage, we encountered a severe storm and practically

everyone suffered severe sea sickness. In our cabin of 16, only two of us

remained healthy. We were responsible for gathering food for all the others.

We continued

collecting meals for 16 men, eating most of it ourselves. I became friendly

with one of the

ship's sailors who took me on a tour of the entire vessel. The huge turbines

were most

interesting to me. At Iceland our security was assumed by two Royal Navy

destroyers who

accompanied us south to the river Clyde in Scotland.

From the docks in Grenock on the Clyde we went by train to Bournemou on the

south coast of England, which served as a holding facility for Canadian airmen.

We were housed in a commandeered hotel for a few days until details were organized.

During this time we became familiar with the small, swift trains, the strange

currency, and the general wartime austerity. We were surprised at the general

cheerfulness and friendliness of the

citizens, who had suffered bombing, rationing and considerable relocation.

Several of us were then posted to RAF Mildenhall located in Suffolk.

Mildenhall was an old RAF airdrome from the 1930’s

with fairly good hangers

and barracks. The Canadian 419 squadron was forming up there but most

of the ground crew were still RAF personnel. As a corporal I was put in charge

of one twin-engined Wellington bomber. I had one English and one Scottish

mechanic as well as two Canadian airframe specialists. This airplane had the

old style, poppet valve, Bristol Pegasus, nine-cylinder radial engine. As they

were continually used to bomb the distant German cities, they required a lot of

work, especially on the engines to ensure their reliability. Newer sleeve valve

engines were gradually replacing the old ones, so I was sent on a two week

training course to the Bristol engine factory to learn about them. The RAF

administered the course and it was an excellent one, as were all their courses

I had the opportunity to experience. We were boarded out in private homes,

two or three to a house. A visit into downtown Bristol one Sunday gave me

my first real look at what German saturation bombing could do. The entire

centre of Bristol was a devastating mess.

with fairly good hangers

and barracks. The Canadian 419 squadron was forming up there but most

of the ground crew were still RAF personnel. As a corporal I was put in charge

of one twin-engined Wellington bomber. I had one English and one Scottish

mechanic as well as two Canadian airframe specialists. This airplane had the

old style, poppet valve, Bristol Pegasus, nine-cylinder radial engine. As they

were continually used to bomb the distant German cities, they required a lot of

work, especially on the engines to ensure their reliability. Newer sleeve valve

engines were gradually replacing the old ones, so I was sent on a two week

training course to the Bristol engine factory to learn about them. The RAF

administered the course and it was an excellent one, as were all their courses

I had the opportunity to experience. We were boarded out in private homes,

two or three to a house. A visit into downtown Bristol one Sunday gave me

my first real look at what German saturation bombing could do. The entire

centre of Bristol was a devastating mess.

I remained at Mildenhall all that spring and summer. More and more Canadian

groundcrew arrived to replace the RAF personnel until we were more or less on our own.

I should mention that we learned quite a lot from these experienced men, and while we had our

differences, generally, we got along quite well.

One of my very vivid memories of that winter is of a Wellington with a new

crew on a training flight crashing in the woods right near our hut. The plane burst into flames

and, tragically, all the crew burned to death with all of us looking on helplessly.

Our planes flew bombing raids normally only at night, but on February 12

of ‘42 a different situation occurred. Two German pocket battleships were

attempting to come through the North Sea.

Several of our Wellingtons were

hurriedly bombed up and otherwise prepared for this daylight operation.

Wing Commander John "Moose" Fulton, our commanding officer, came out to my

aircraft and said, "corporal, do you know how to boost up the power of

these old Peggy engines? I'm taking this kite (British slang for aircraft)

because it is the oldest one in the squadron". I said, "yes sir, I know

how to do it, but if I do, you can blow them quite easily". He said, "do it,

corporal", I'll risk it, a bit more power may save my life if I get into

a tight spot". I did as the Wing Commander requested' luckily he came back

safely, although the engines never did sound right after that. Fortunately,

this kite was soon retired from operations and I received a new one with

the modern Hercules engines. Sadly, it was shot down on its second trip

over Germany.

Several of our Wellingtons were

hurriedly bombed up and otherwise prepared for this daylight operation.

Wing Commander John "Moose" Fulton, our commanding officer, came out to my

aircraft and said, "corporal, do you know how to boost up the power of

these old Peggy engines? I'm taking this kite (British slang for aircraft)

because it is the oldest one in the squadron". I said, "yes sir, I know

how to do it, but if I do, you can blow them quite easily". He said, "do it,

corporal", I'll risk it, a bit more power may save my life if I get into

a tight spot". I did as the Wing Commander requested' luckily he came back

safely, although the engines never did sound right after that. Fortunately,

this kite was soon retired from operations and I received a new one with

the modern Hercules engines. Sadly, it was shot down on its second trip

over Germany.

The attack on the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau was to cost 419 squadron two of the three crews that did find the ships which were very heavily protected by Luftwaffe air cover.

In the middle of the summer, all the aero engine corporals were called

to the adjutants office and offered the chance to remuster to flight engineer for the four-engined

Halifax bombers that we were going to be issued the following spring. We were given a few days

to make a decision. I was extremely tempted but I had promised Bernice that I would always

stay in the groundcrew, also by this time I had seen so many aircrew go missing, the glamour

just wasn't there anymore. Therefore I passed on the offer.

An interesting note on the fate of the four who did remuster (they were all friends of mine);

one was killed in a training accident, one was shot down over Berlin and spent the rest of the

war in a prison camp, one I lost track of, but the remaining one, Ken Johnston, did three tours

of operations and then became a Group Captain in charge of the training of all the flight

engineers in No. 6 Bomber Group.