A Daughter puts Voice to Her Father's War Time Experience

Barbara Trendos takes an emotional journey back in time to write

about her father's war experience

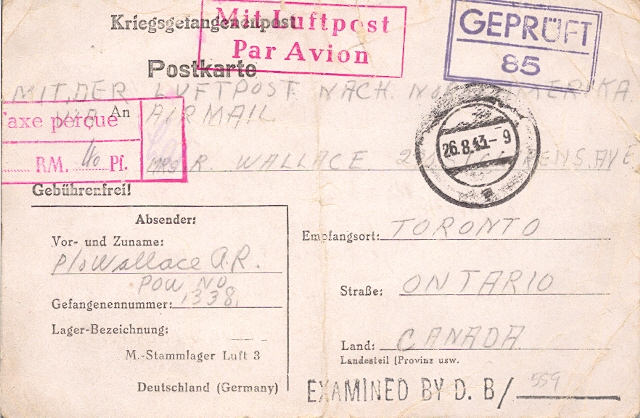

It was one night over thirty years ago when Dad first brought out that plain, beat-up file folder. Although I can’t recall what prompted him to do so, I clearly remember sitting on the shag carpet at the foot of his easy chair in front of the fireplace in our family room. The file was full of telegrams, war correspondence, and all the letters and Postkartes he’d written to Grandma from the prison camp. They were handwritten in pencil, the letters on long skinny, flimsy stationery with Kriegsgefangenenpost (Prisoner of War Post) printed at the top, each beginning “Dear Ma” and faintly postmarked 1943 or 1944, some with sections blacked out by a zealous Gepruft (censor), many worn through on the fold lines.

Fragile pieces of history.

Of course, I knew Dad had been in the Royal Canadian Air Force, and that he’d been a PoW in Germany, but until that night, it hadn’t been real to me. Dad, who was in his sixties at the time, didn’t mind me reading his personal letters, and just chuckled when I commented on his dreadful penmanship, and even worse spelling, grammar and punctuation! It occurred to me later that they were probably the first letters he’d written in his life. And when I got to the parts where he mentioned the girls he’d left behind in Toronto, Halifax and England—that’s girls plural—I kidded him mercilessly. It’s hard when we’re young to conceive that our parents were ever our age and doing—heaven forbid—some of the things we’ve done.

I didn’t see the letters again for over twenty years—until I asked for them. I think that my father, Albert Wallace, in his own unassuming way, always wanted to leave a legacy of his war experiences. As a fellow World War II researcher in Denmark recently said to me, “…he [your father] has a message, actual also in 2011, to be told. Freedom and democracy cannot be taken for granted.” And although Dad was a business executive in his working life, he just wasn’t the book-writing type. So, at about age seventy, my father, ever the sociable fellow, began giving interviews for newspaper articles and TV documentaries, and that led to his giving presentations to high school students and historical organizations through The Memory Project, a wonderful initiative led by the Historica Dominion Institute. He obtained a copy of his RCAF service file from the government; began audiotaping parts of his story; and wrote his profile for various air force related websites.

Dad would occasionally show me one of his taped interviews or give me a copy of an article, and along the way it occurred to me that his memories deserved better than to end up a pile of forgotten paper and tapes in a box somewhere collecting dust. Without any vision of where I was going to go with any of it, I began collecting what he gave me, and even transcribing some of his interviews and talks. And as I did so, his story began to unfold more clearly in my mind.

* * * *

Grandma was probably in the kitchen making supper, or perhaps she, Grandpa and daughters Eleanor and Betty were already eating around the kitchen table when they heard the sharp rap on the front door and someone went to answer it. For a family with a son and brother overseas with the Royal Canadian Air Force during the war, the very sight of the telegram delivery boy on the porch must have unleashed feelings of dread.

Dad and the other six members of his Halifax bomber crew had been on a raid on Germany the night of May 12, 1943, and had failed to return to their Squadron base in the north of England. The Squadron wing commander would later write to Grandma that “the raid was the heaviest and most successful ever made by the Air Force”—as if those words could possibly console her. Dad was, after all, her only son. And after offering up glowing words about Dad and his contribution to the Squadron, the letter went on to say, “Your son’s kit and personal effects have been collected and forwarded to the Central Depository, Colnbrook, Slough, Buckinghamshire, who after completion of necessary details, will communicate with you regarding their disposal. May I extend my sincere sympathy on your loss and express the hope that better news may follow. ” The desensitized, show-must-go-on nature of the wing commander’s words notwithstanding—how many times did the poor man have to write the same message to anxiously waiting parents?—news indeed followed; however, it took several weeks.

The wait for Grandma and Grandpa must have been torture, Albert’s face smiling out of the framed picture in the living room, him sporting his RCAF officer’s cap and his Air Gunner’s badge. Only twenty-two years old. They were so proud of him.

The telegram, delivered at 1:14 p.m. on June 4, told them Dad was alive. He was a prisoner of war.

The wait for Grandma and Grandpa must have been torture, Albert’s face smiling out of the framed picture in the living room, him sporting his RCAF officer’s cap and his Air Gunner’s badge. Only twenty-two years old. They were so proud of him.

The telegram, delivered at 1:14 p.m. on June 4, told them Dad was alive. He was a prisoner of war.

Dad’s aircraft had been shot down over Germany in the early hours of May 13, 1943. He and four of the crew had bailed out of the burning aircraft, using their white silk parachutes for the first and only time. They’d never had so much as a practice jump. Mac the pilot, and Dave the wireless operator, both of them Dad’s crewmates and friends, were not so lucky: they crashed with the aircraft and died, likely having sacrificed their lives so Dad and the others could get out. I have a worn snapshot of Mac, and every time I look at it, I get a lump in my throat. Forever young, so handsome in his pilot’s tunic, such sparkle in his eyes. For Dad, it was the beginning of a two-year chapter in his life spent under armed guard and behind barbed wire.

For the next twenty months, it was Stalag Luft III, the Allied air force officers-only prison camp near Sagan (now Zagan, Poland) from which the “Great Escape” famously took place. Germany was party to the Geneva Convention, which required humane treatment of prisoners of war, so the German Luftwaffe (air force) didn’t mistreat the men. Being officers helped too, to some extent. Regardless, rations were meagre, stomachs were never full from the meals the men had to prepare for themselves, and life was a never-ending and meaningless drone, save for the spotty delivery of mail from home and whatever entertainment the men themselves could drum up.

Stalag Luft III: Dad and some of the lads

It was far from Hogan’s Heroes. And after the Great Escape took place in March 1944, when Hitler ordered the execution of 50 of the 76 escapers to make them pay for humiliating the Third Reich with their brazen escape, the prisoners lived under a terrible pall. As the men mourned their lost friends and roommates, camp activities were cancelled, the lifelines of Red Cross food parcels and mail from home were cut, and the knowledge that Hitler had so boldly flaunted the Geneva Convention didn’t bode well for the rest of the men should Germany fall.

Then, in the final months of the war, Dad and his fellow prisoners were forced to endure two marches to flee the advancing Russian army. It was January 1945. Their German captors evacuated them from Stalag Luft III at short notice, on foot, in the middle of the night, with only what they could wear and carry. Dad had sewn a backpack from a blanket. Six inches of snow on the ground. Sub-zero temperatures. Already hungry from months of restricted rations. Little to no order or organization. No provision to feed the prisoners. The men traded cigarettes for food with civilians, slept in fields huddled together for warmth, and dreamed of living long enough to see another sunrise. They would march 250 kilometres over three months before British soldiers finally liberated them on a sunny day in May 1945. Along the way they suffered frostbite, sickness, malnutrition, friendly fire. Many didn’t make it.

Dad was one of the lucky ones.

Seven or so years ago when I went part-time, I decided to stop hiding behind the growing, disorganized jumble of information in my banker’s box labelled “DAD” and begin turning it into something—anything—more. As I read through a pile of letters that students had written to him about his presentations, I was impressed with their interest in his experiences, their thoughtfulness and, most of all, their thankfulness. I realized that in the spirit of “Lest We Forget,” they were the audience who most needed, and wanted, to hear Dad’s and other veterans’ stories before they were lost forever. But I knew as well that I would have to make his experiences real enough for them to identify with him, especially his young age at the time, to put themselves in his shoes, engaging enough to hold their interest, and easy to read.

"..my portal, like no other... "

Dad’s letters came to mind and I decided to make them the backbone of what I came to call my “Dad Project.” I retrieved the letters from him; sorted them; slipped each into an archival-quality protector; read and reread them from start to finish; and transcribed them. I have spent a lot of time with those letters. They are my portal, like no other, to that time and place, and became one of my keys to getting to know Dad as a young man. They told as much of a story by what they didn’t say as by what they did say. Did I ask Dad for permission to incorporate his letters into my writing? Well, no. I presumptuously subscribed to Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper’s philosophy that “it’s easier to ask for forgiveness than it is to get permission.”

But my grand idea of making the letters central to my writing quickly revealed itself as flawed, or at least more studded with hurdles than I’d anticipated.

For one thing, they covered only the time period that Dad was actually in the prison camp—one of the more dramatic parts of his war-years story,

to be sure—but I had decided that I should tell his whole story, from enlistment to liberation. That lofty goal meant I that I needed to create a detailed timeline,

and to fill in several significant gaps: his enlisting in Toronto; living with other new recruits packed into the Coliseum Building and Horse Palace at the

Canadian National Exhibition grounds; training at a station in southwestern Ontario; being awarded his King’s Commission to Officer; shipping overseas;

flying air operations out of his Squadron base in England, including that last, fateful mission; and finally, marching across Germany to freedom.

But my grand idea of making the letters central to my writing quickly revealed itself as flawed, or at least more studded with hurdles than I’d anticipated.

For one thing, they covered only the time period that Dad was actually in the prison camp—one of the more dramatic parts of his war-years story,

to be sure—but I had decided that I should tell his whole story, from enlistment to liberation. That lofty goal meant I that I needed to create a detailed timeline,

and to fill in several significant gaps: his enlisting in Toronto; living with other new recruits packed into the Coliseum Building and Horse Palace at the

Canadian National Exhibition grounds; training at a station in southwestern Ontario; being awarded his King’s Commission to Officer; shipping overseas;

flying air operations out of his Squadron base in England, including that last, fateful mission; and finally, marching across Germany to freedom.

Much research was definitely going to be in order, as were interviews with Dad, by then eighty-seven years old. (I knew of course how fortunate I was to still have him to interview.) Then too, I had to find a way to connect the letters with more than Band-Aids to move the story along and help it flow. I thought about using narrative to link the letters and bridge gaps, but I didn’t want long passages to detract from my objective of making it easy-to-read, not to mention that I was intimidated at the prospect of writing narrative. Although I wrote corporate communications for a living, I saw myself as a rookie writer on a personal level. Around that time, I came into a copy of an actual wartime log book meticulously kept by a fellow Canadian prisoner Dad had known in the camp—Johnny—and now displayed in an Air Force museum in British Columbia. As I flipped through Johnny’s handwritten entries and drawings in this amazing resource, and discovered all kinds of rich details I could use, I had my epiphany: I would write a mock journal in Dad’s voice and incorporate his letters for interest. My presumption, I realized, was growing in leaps and bounds as my writing began to morph and move into unknown territory, to me anyway, as far as genre: a hybrid of memoir and story mortared with research. Perhaps even a beloved daughter would not be able to get away with this.

But I was determined to try. Continued in Part 2

Our Thanks to Barbara Trendos for sharing her father's story

"Originally published on the website Memoir Writing & More

and reprinted here with the permission of Allyson Latta."

www.allysonlatta.ca

and reprinted here with the permission of Allyson Latta."